Earlier this week I did a studio visit with an artist who lives up the road from me. Their studio was massive — warehouse scale, glitter on the floor everywhere, huge buckets of paint. And racks and racks of finished paintings, some rolled-up, others boxed for shipping, and lots more just stacked against each other — many over 20 feet tall or wide. It was in radical contrast to my studio where, because so much of my work is digital, there isn’t a lot of visible history. And definitely no glitter.

It triggered in me a desire to look back at some of my older work — things I may have produced, but since filed away or put into my own, more moderate, storage. (A big NAS hard drive array is not very dramatic to look at.) Or perhaps shared on social media, but then lost to the cloud of the IG scroll.

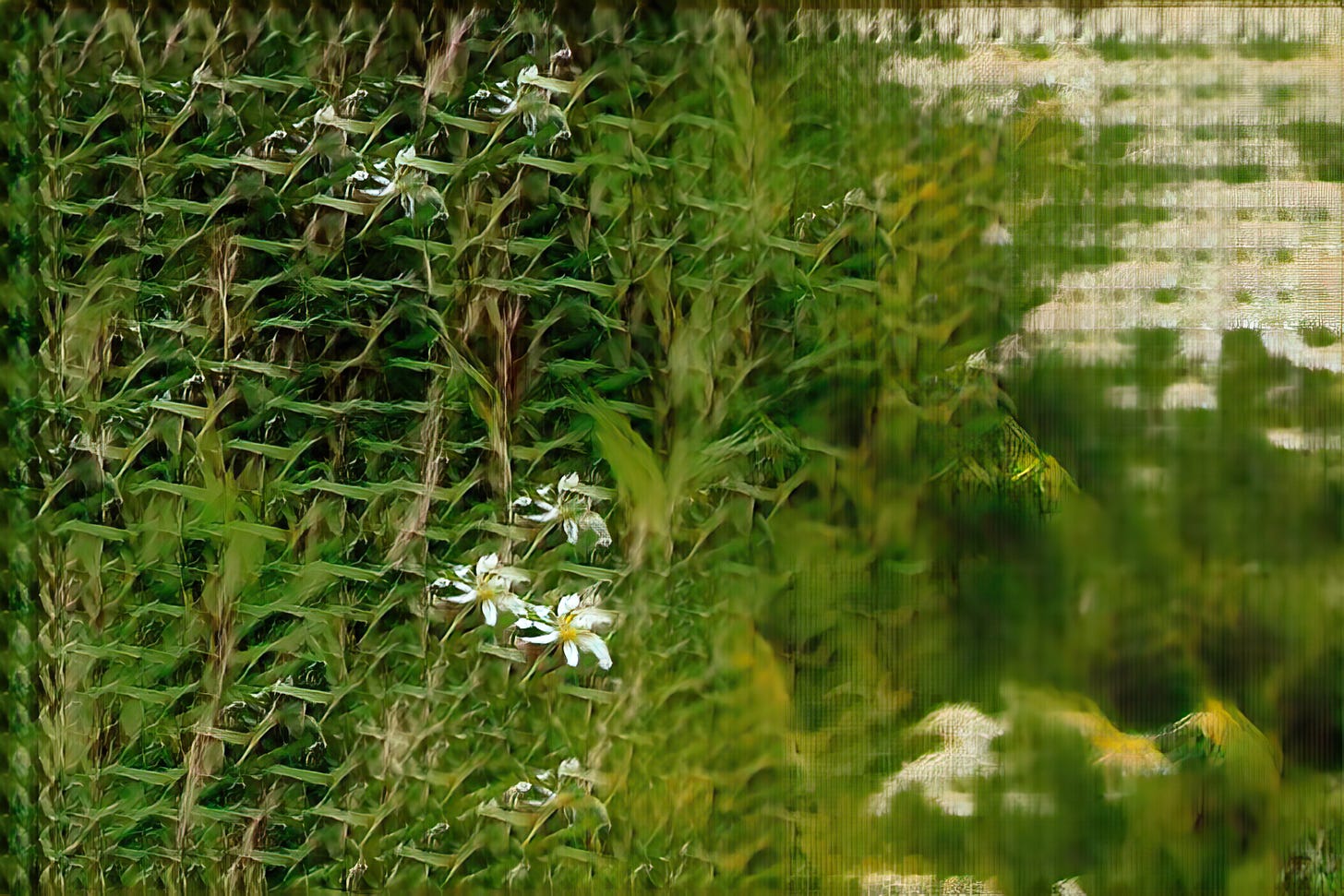

And as I rifled through my hard drives I stumbled upon a series I did around the start of the COVID pandemic. The work began in August 2019 and was completed in March 2020. It was based on a series of pictures I took of grasses and wildflowers at my farm in Upstate New York, which I then used to train my AI / GAN.

Remembering now, as I looked at them again with fresh eyes, I really liked the work. They had a strangely dense complexity, very different from other AI-based works that I had been making at that time. In fact, the first thing that came to mind when I created them, was that they were tapestries. They reminded me of the Unicorn Tapestries that I’d seen pre-pandemic at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Cloisters galleries.

I did, in fact, then start to explore the idea of turning my work into something fabric. But that ended up being something quite different. (See my collaboration with Susan Yelavich for our Darns series of work.)

The grasses, however tapestry-like they may seem, also have a mixture of the photographic and the machine-like materiality of AI / GAN images. Repeating elements, foreground/background simultaneity, and a density that draws the viewer in.

There’s a hallucinatory quality that, for me, really captures not just the abundance of nature, but its awe and danger. We can delude ourselves, sometimes thinking that we have power over nature. Bur really, nature is just one step away from overwhelming everything that we have created — even if it is something as seemingly benign as a grassy field full of wildflowers.

That tension between the beauty and danger of nature is echoed in our relationship to emerging AI. To some it seems to offer untold benefits, but simultaneously there is a growing chorus of those warning that it could upend civilization in untold ways.

Is there also a COVID aesthetic here? At the time these were made we were all afraid to go out — and so the danger of nature and the unknowns that lurked outside was a big part of our psychology. We had all turned into inward nesters, trying to make our homes more comfortable as we settled into the idea that we might be home-bound for a while. And so tapestries, wallpaper, and ways of wrapping something comfortable around us, likewise, were part of that moment. Making COVID-era work wasn’t what I was seeking to do, but for me, this work does now feel like it came from a particular moment in time.